Every venue seems more bizarre than the last. Joseph K visits a number of people and even the court itself in pursuit of his self defense. Once he is arrested, an examining magistrate inquires into the case against him – and the process gradually merges into the verdict.

He never discovers the precise charge which is made against him. Of course, no trial in the ordinary sense of that word takes place. He appeals to all forms of bureaucratic authority for help and clarification, but gets nowhere. Indeed, it gets worse with each of his efforts to understand or do anything about it. Joseph K’s offense is never explained to him, and the illogical nature of his helplessly vulnerable condition is pursued relentlessly throughout the narrative. Needless to say, it has also become commonplace throughout the world ever since – from Franco’s Spain and Pinochet’s Chile to China, North Korea, and today’s middle-East. The novel opens with a sentence which has become famous – heralding the nightmare to come: “Somebody must have been telling lies about Joseph K, for one morning without having done anything wrong, he was arrested.” This is the ‘knock on the door’ which was to become an everyday experience for millions in the years that followed in the totalitarian worlds of Stalin’s Russia and the Nazi period of German’s history. It deals with the arbitrary nature of power threatening the freedom of the individual and the crushing of every attempt to understand its workings. It is a novel which seems to give an amazingly premonitory account of the horrors in the modern totalitarian world.

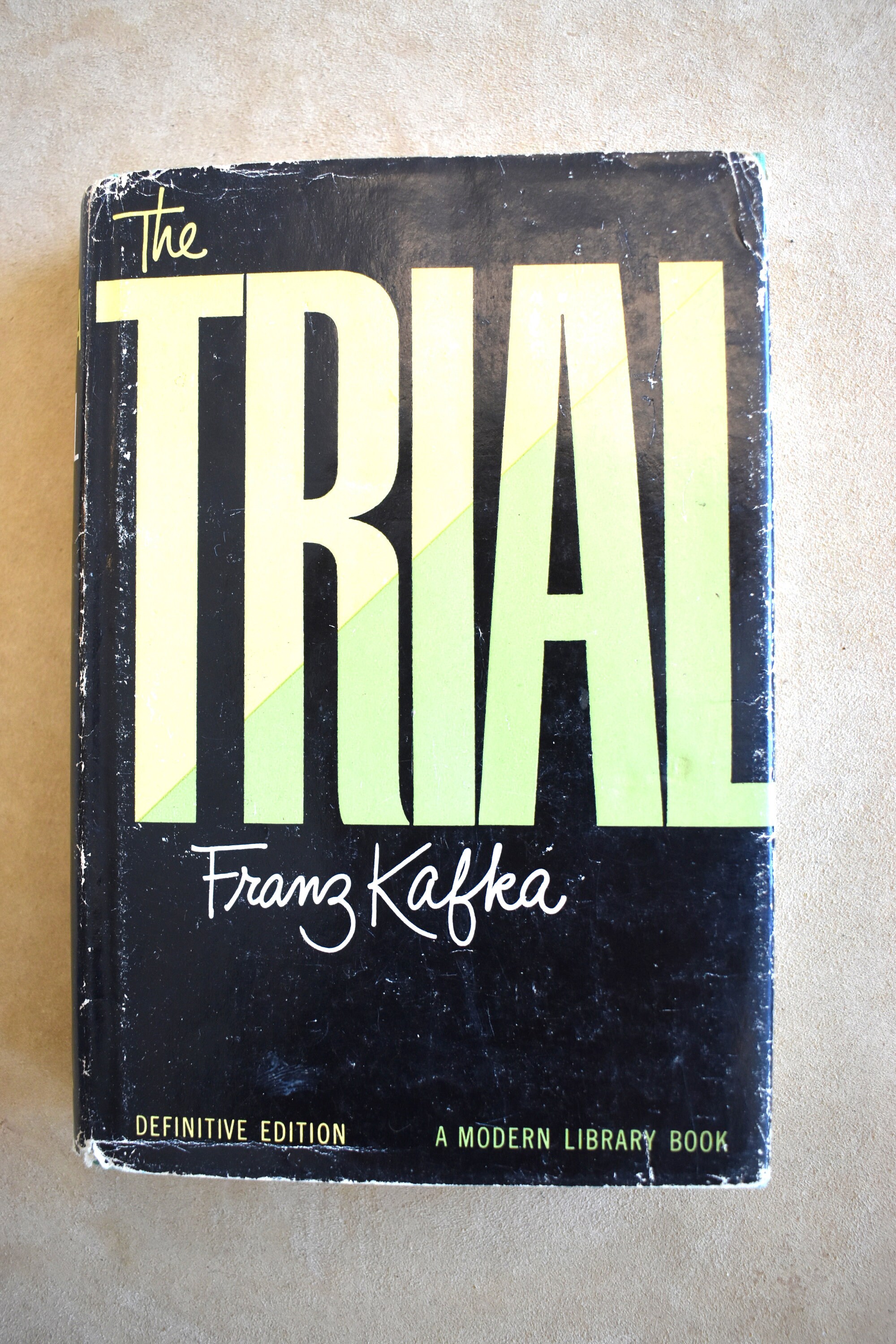

The parts were assembled and published by his friend Max Brod in 1925, the year after Kafka’s death. But even so, its chapters were kept in separate folders and he gave no indication of the order in which they were to appear.

Most of his other work is renowned for being fragmentary and incomplete. The Trial was the only novel Kafka ever more-or-less completed during his own lifetime.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)